(Catherine Austen’s DIY Writing Workshop #2)

Here’s a “Build your Setting” handout and a mini-lesson that you can adapt into your own writing workshop to do alone or with your class or writing group.

Who cares about setting?

Setting is your story’s time and place, the physical world where your scene occurs. You can help the reader build an image of that world with a few select words. Sometimes more than a few.

“Jane stepped out of her house.”

Perhaps that’s the first line of your story. The reader is with you, picturing something like this:

But if this is the house that Jane stepped out of…

… you’re going to need to write more than “her house.” Because no reader is going to spontaneously picture that.

There’s a funny thing about fiction. If the reader can picture a scene, they’re more willing to believe what happens in it. If they can’t picture it, they’re less likely to believe your story.

When Jane slams the door of her house and it falls off the hinges, it’s kind of hard to believe if we’re imagining the suburban house. But if we’re picturing the rusty shack, the unhinged door reinforces the scene and makes it even more believable. And that makes us want to know more about Jane. Why did she slam the door? Where’s she going? Does she really live in that squalid hut?

Squalid. Rusty. Hut. Shack. We build our settings with words. With adjectives: a tiny tumbledown house, a rusty old house. With nouns: a shack, a dump, a hovel. And what if Jane stumbled or crawled or slithered out of her hovel? Those verbs paint a different picture still. Just a few words are enough to help the reader paint a mental picture.

So yes, readers care about setting.

Build your setting

In creating a setting, you can simply start writing a scene — try one where a character is moving through the setting — or you can build it, bit by bit.

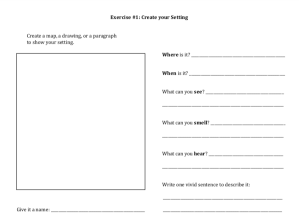

Use this handy handout to help build your setting.

Start with a real place — your school, your friend’s swimming pool, the fancy hotel you were at last summer, or somewhere in the news or in a history book. Or invent a setting unlike any seen — an ice-field on an alien planet, the gates of Hell, a virtual paradise. In a pinch, take an ordinary setting and add something extraordinary to it, e.g., your office during an alien invasion; the local park when a tornado hits; your basement at 3am.

Ingredients of Setting

In building a fictional setting, start with a few basic sets of questions:

Think about time

In creating a setting, first ask: When does your story take place?

- What’s the historic time? (2019? 1600? 2840?)

- What’s the calendar time? (Ottawa is a completely different setting in summer and winter.)

- What’s the clock time? (Your kitchen is a different place at 7:00 p.m. during a dinner party vs. 3:00 a.m. in a thunderstorm when you’re alone, searching for a flashlight.)

A good story includes a few details that reflect the times. This is all the more important if your story is set any time but now. If your story is set in the future or past, you’ll need to make sure the reader knows it.

Think about place

“Place” in a story can be an entire galaxy or a single classroom.

Setting includes the culture of a place — its politics, its architecture — and the nature of a place — its weather, its wildlife. But don’t feel like you have to write an entire history and travel guide. Just let time and place inform your story.

That means being factual. If your story is set near the equator, don’t have the sun still shining at 9:00 p.m.

If you’ve been to an unusual place — a foreign country, a submarine, a racetrack — and you know what it’s like and how people behave there, consider it as a setting for a story. Readers appreciate authentic details.

Think Mood

If you are writing a story about a boy shipped off to his uncle’s for the summer, does he arrive here:

or here?

The shack setting immediately builds a mood of menace. This is going to be a weird summer for that kid. Maybe awesome, or maybe horrifying, but definitely extraordinary.

But you don’t have to have a creepy shack to build tension. You can build mood with any sensory details that trigger emotion. The suburban house becomes frightening in the night when there’s a creak on the stairs, and the knife block on the kitchen counter has one knife missing. Eek!

Think of all the senses

Humans are visual creatures, but if you can add some of the other senses — the feel of a carpet on bare feet, the smell of cookies in the oven, the tinkle of piano keys in a distant room — you will build a richer setting. The reader will become fully immersed and far more invested in your scene.

But don’t overload the reader with information. We don’t need constant sensory input any more than we need a list of furniture in a room or a history of how the house fell into disrepair. Just enough to paint a picture.

And you don’t have to paint it all at once. You can show your setting as your character moves through it.

Remember Character

It’s how your characters feel about your setting and what happens to them there that matters most. So, as you’re building your setting, think of who might be there and what they might be up to.

And how do they feel about the setting? To me, the abandoned house is creepy. But if your character is a mouse, or a ghost, or a photographer of abandoned houses, that setting might be a happy one.

Once you build your setting, you’ll probably instinctively start to bring characters into it. But you can Start with a Character and then come back to setting, if you prefer. Or go from here to there and back again.

Ready?

Forcing yourself to come up with setting details often gives you ideas for what could happen in a story. Just answer all the questions and fill in all the blanks. You’ll amaze yourself with your creativity.

You don’t have to know everything — you’ll develop your setting as you write your story — but after this exercise, you’ll know enough to let the reader picture your setting in an opening scene. (More on that in another workshop.)